On the right day, even the popular Copperas Pond feels like a secluded backcountry oasis.

Go there, as I recently did, when the snow is blowing and the temperatures struggle to stay above zero. It's possible, even a mere half mile from the road, for the intrepid afternoon explorer to feel alone with the mountains, trees, and animals.

Perhaps there's a hermit in all of us.

My inner hermit began to stir the first time I saw Copperas Pond, a small waterbody tucked just out of sight behind the eastern wall of Wilmington Notch, some 18 years ago. I drove to the Adirondacks from Binghamton with three of my friends on the word of a tattered New York state road map that promised high peaks. We had no idea where we were going, really. The worn, wooden sign at the Copperas Pond trailhead offered us some direction.

We charged upward and over the steep ridge that secludes the pond from the busy road below. That was my first taste of being in the mountains, my first glimpse at the stark and lovely contrast of peaceful quiet and rugged forest. There was no turning back.

That little pond became my basecamp for adventure in the High Peaks. Since I was new to the mountains, I never even considered hitting the trail by myself. A lot has changed since then. The peeling yellow letters on the trailhead sign now sharply and brightly point the way, the lean-to on the northern shore doesn't have piles of garbage behind it, and I often hike alone.

The first two speak to the hard work of those who help maintain trails in the Adirondacks. The part about hiking solo was a personal necessity — I simply grew weary of having my plans become unhinged by people who didn't feel the same pull toward the mountains that I felt. So one day I decided to hike Porter Mountain by myself. The experience was a turning point, and since then I've not only embarked on 15-mile day hikes by myself, I've also camped alone.

Whenever I'm in the woods, my mind feels free to cartwheel in any direction it pleases. There's no better environment for sorting out the barrage of thoughts life brings, and there's no better place to turn that barrage off. Sometimes, when I'm out there, I consider what it would feel like to never return to civilization, to just hurl myself through the forest until I found a spot to settle down in. It would mean getting to know the habits of my new neighbors — the birds and the squirrels and the moths. It would mean falling asleep to the chatter of insects in the summer and the commanding stillness of winter. Yeah, I could get used to that.

Perhaps that's the hermit in me talking.

In the Adirondacks, that hermit had a name. It was Noah John Rondeau, the self-proclaimed mayor of Cold River City (Population 1). The remote Cold River flows between the Western High Peaks and their eastern counterparts. It was there, miles away from polite society, that Rondeau built his cabin on a bluff in the woods in 1929.

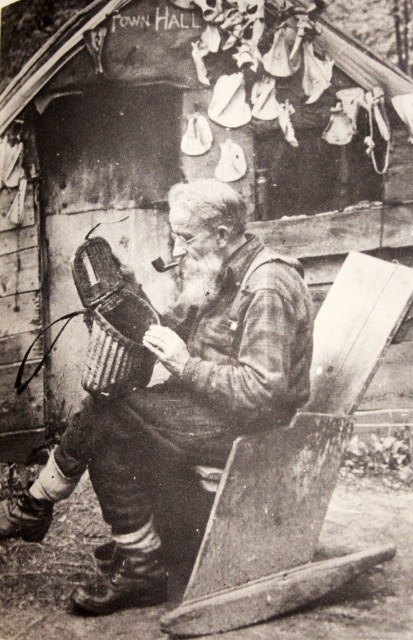

The man must have been a sight to behold. A story in the 1946 October-November issue of New York State Conservationist magazine described his apparel, which often included deer hides, bear teeth, and a long bow. When the story ran, Rondeau was 63 years old and had been living in his Cold River town hall for 17 years. With his beard and tattered clothing he looked the part, for sure, but he also lived the part. Rondeau hunted and fished for his food, filtered his coffee through an old sock, and had his own made-up language that people are still marveling over.

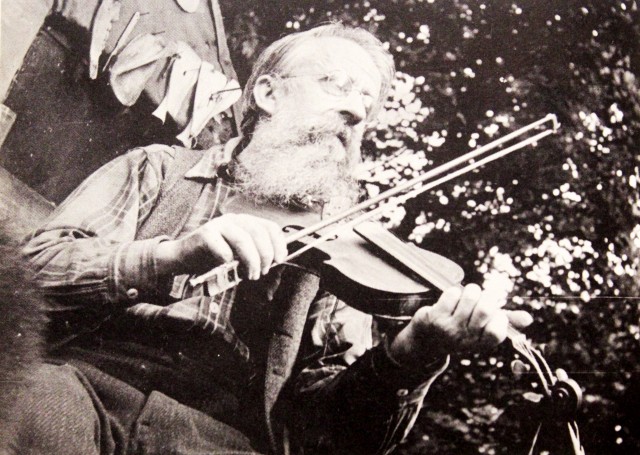

My own inclination toward becoming a hermit is tempered by my inclination toward people. But as much as I like being social, I also need time by myself, preferably in the mountains. Rondeau liked people too, as stories regarding his willingness and ability to entertain will attest. It seems the man became something of an attraction as word got out about his hermitage. People visited him during their treks into the woods and were generally welcomed. There are plenty of photos that speak to the merry times he shared with strangers. There's Rondeau playing a fiddle, showing off his homemade telescope, or preparing a trout dinner. To facilitate these interactions, he even rerouted part of the Northville-Lake Placid trail so it went by his home.

Not all visitors were welcome, though. Rondeau's presence raised the hackles of some, and an ongoing feud between the hermit and the Department of Environmental Conservation ensued. To be clear, Rondeau harbored disdain for many of society's trappings — elections, big business, inherited wealth, and economics were among his most scorned — which is probably why he took to the wilderness to begin with.

The trouble started in 1910, when DEC employees accused Rondeau of starting a brush fire near the site of his future cabin. They imposed a $9 fee, the cost of extinguishing the fire, which Rondeau fought and likely never paid. Other spats with conservation officers occurred, one of which put the hermit in jail fo a short time, but none of them amounted to much. It seems the run-ins were just another part of life in Cold River City.

After a storm in 1950 caused massive blowdown in the Western High Peaks, Rondeau was forced to evacuate the woods and re-enter society. Adjusting to his new life must have been difficult for him. He lived in several places, including Wilmington, Lake Placid, and Saranac Lake, and held a number of odd jobs in the region. Among them were a position at the now-defunct Frontier Town theme park and a stint as Santa Claus at Santa's Workshop in Wilmington. I can just imagine his reaction when a ne'er-do-well kid, thinking he had the mall Santa farce figured out, pulled on his beard, expecting it to come free.

Rondeau's health gradually deteriorated until his death on August 24, 1967. Sadly, his final wish to be buried at his hermitage wasn't granted — he was buried in the North Elba Cemetery instead — but a stone from his Cold River cabin was used as his headstone. The rest of the cabin and some of his possessions are on display at the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake.

Rondeau's story has always spoken to my own affinity for nature and solitude. I'd like to someday make the 7-mile hike to his hermitage in the Western High Peaks and camp in its vicinity. I can imagine waking up there every morning and observing the sights, sounds, and smells of the seasons as they change. The Cold River hermit often wrote about things like hummingbirds and waking to find deer tracks within four feet of his bed. It would be something, I think, to glimpse the world through his eyes, if only for a moment.

Maybe that old hermit in me has the right idea after all.

You don't have to be a hermit to enjoy the Whiteface Region. Go skiing at Whiteface Mountain or explore the beautiful Wilmington Flume trails on foot, skis, or bike.

In related Fame In The ADKs news:

No joke. Will Rogers has seen its fair share of famous entertainers.

A star-studded past with more stars on the horizon.

Lighting the way for the rich and famous.